Image 1 of 11

Image 1 of 11

Image 2 of 11

Image 2 of 11

Image 3 of 11

Image 3 of 11

Image 4 of 11

Image 4 of 11

Image 5 of 11

Image 5 of 11

Image 6 of 11

Image 6 of 11

Image 7 of 11

Image 7 of 11

Image 8 of 11

Image 8 of 11

Image 9 of 11

Image 9 of 11

Image 10 of 11

Image 10 of 11

Image 11 of 11

Image 11 of 11

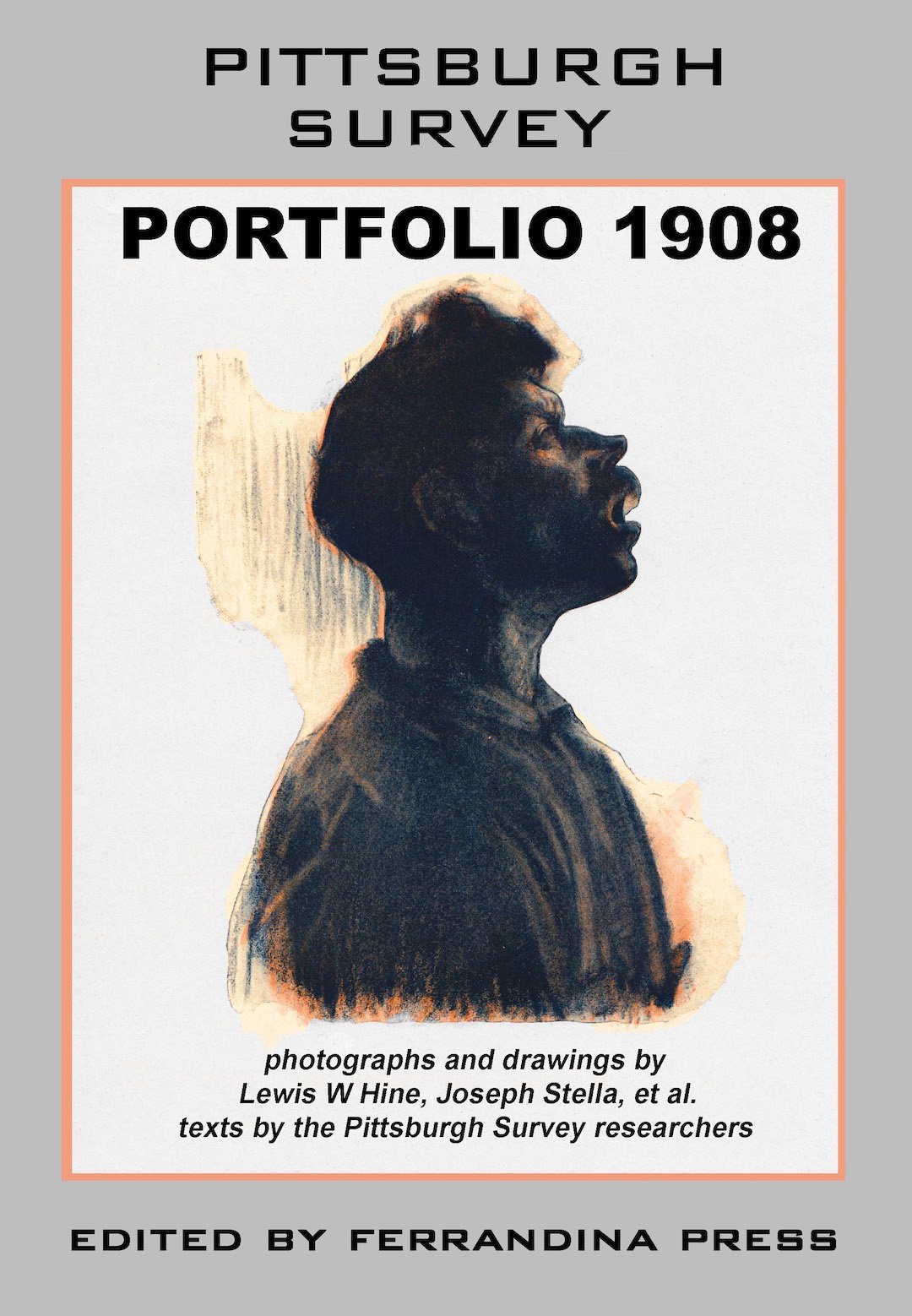

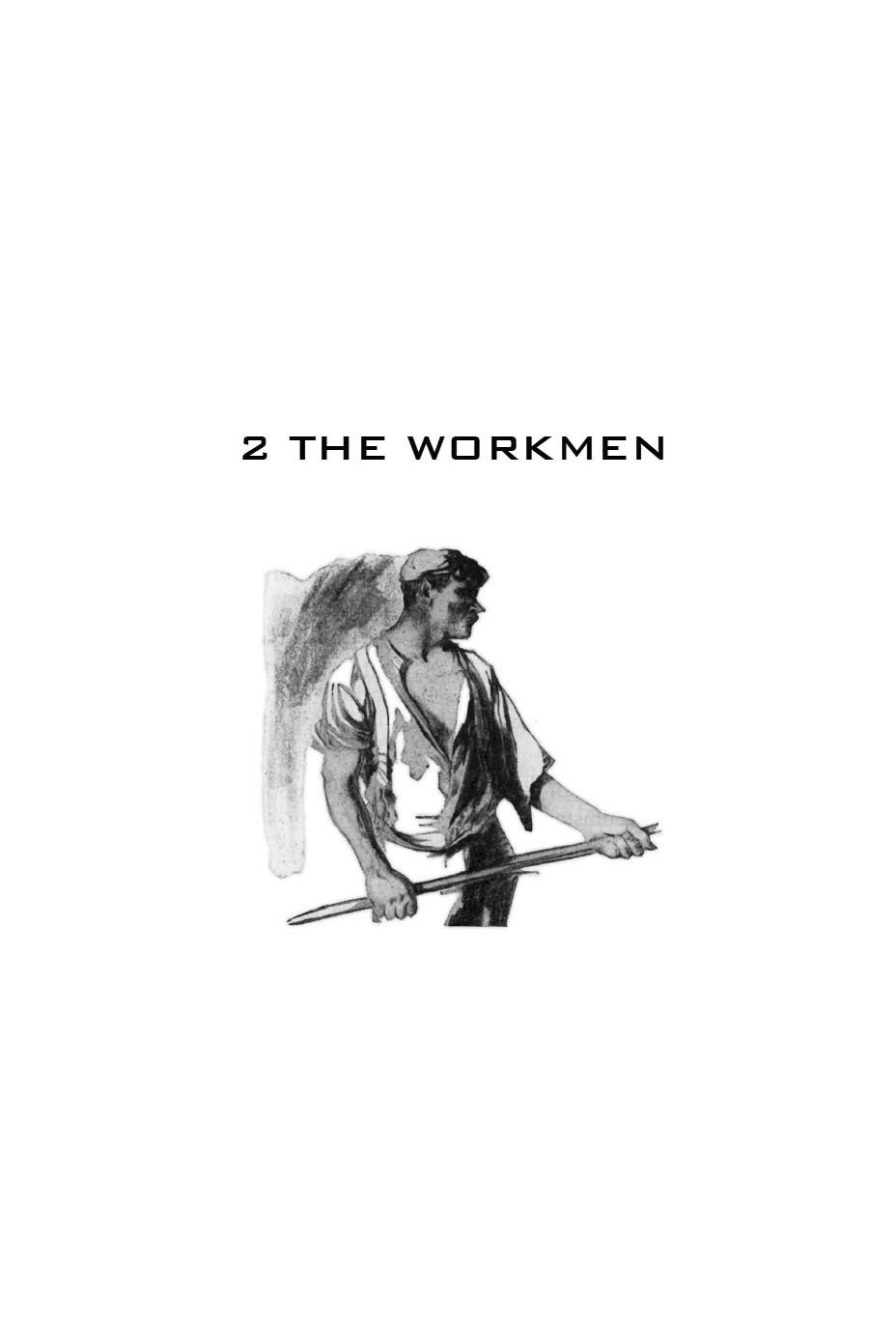

Pittsburgh Survey Portfolio 1908

Ferrandina Press presents a concise introduction to The Pittsburgh Survey, a groundbreaking sociological study conducted during the early years of the Twentieth Century. Portfolio 1908 collects artwork and selected texts from this, the first modern study of working class immigrants in the United States. Enlightening, entertaining and an enrichment of our knowledge of these American ancestors. Photography: Lewis W. Hine, sketches: Joseph Stella; writing by various renowned sociologists of the era.

SKU 90149005

Compiled and Edited by the team at Ferrandina Press

Date of Publication: March 3, 2020

Book Size: 6 x 9 inches, 340 pages

Format: Softcover

ISBN: 9780983056850

*Ships in 5-7 business days

Ferrandina Press presents a concise introduction to The Pittsburgh Survey, a groundbreaking sociological study conducted during the early years of the Twentieth Century. Portfolio 1908 collects artwork and selected texts from this, the first modern study of working class immigrants in the United States. Enlightening, entertaining and an enrichment of our knowledge of these American ancestors. Photography: Lewis W. Hine, sketches: Joseph Stella; writing by various renowned sociologists of the era.

SKU 90149005

Compiled and Edited by the team at Ferrandina Press

Date of Publication: March 3, 2020

Book Size: 6 x 9 inches, 340 pages

Format: Softcover

ISBN: 9780983056850

*Ships in 5-7 business days

MORE ABOUT PITTSBURGH SURVEY PORTFOLIO 1908

Pittsburgh Survey Portfolio 1908 is a compendium that brings together salient texts, photographs and drawings from the publications resulting from the Pittsburgh Survey, referred to as “The Findings in Six Volumes.” This survey, funded and organized by the Russell Sage Foundation, was conducted in 1908-1909. The six volumes of findings were written by some of the most well respected and insightful social researchers of the era, and immediately became the gold standard of progressive sociological work.

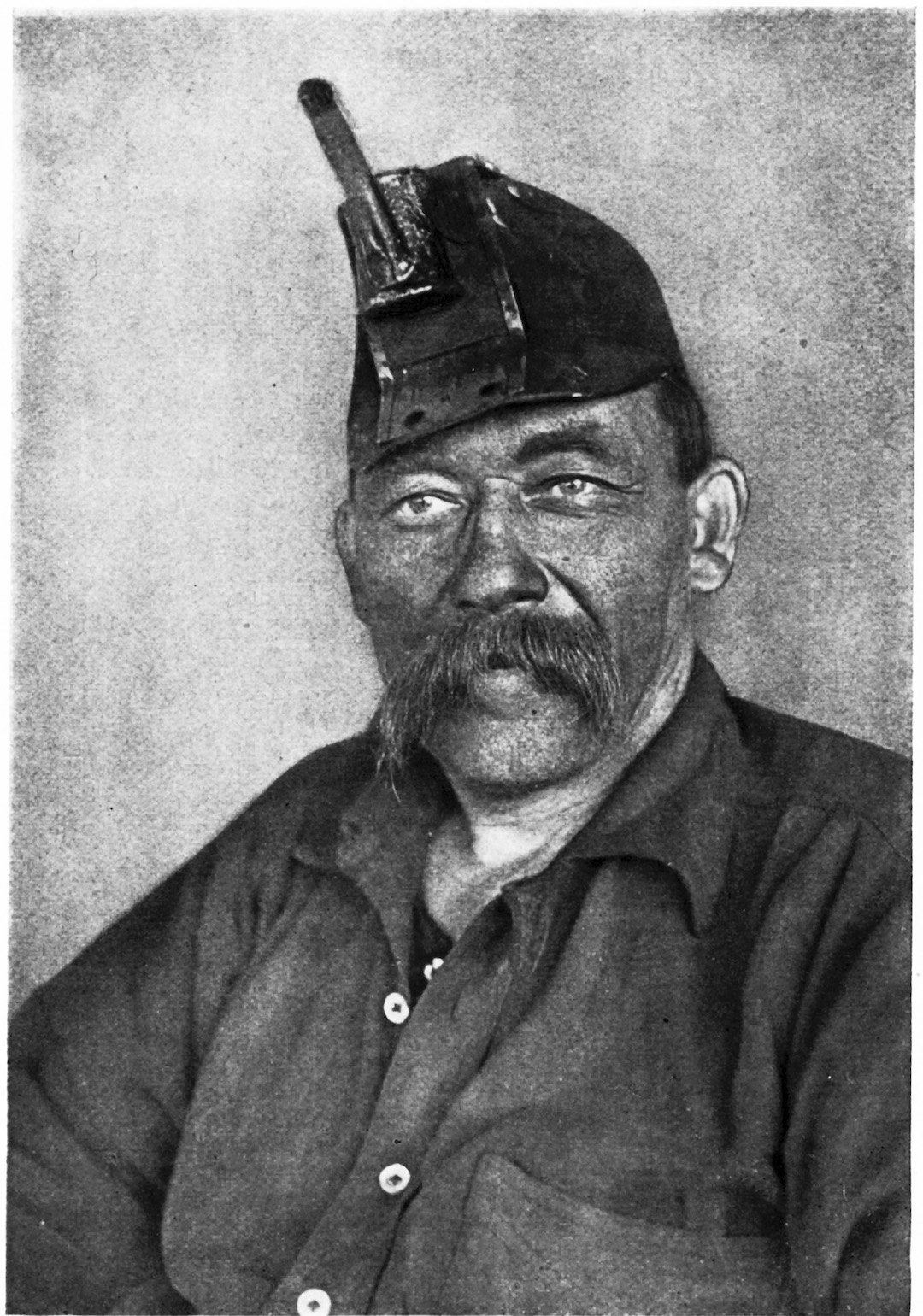

Enjoy this introduction, which as a Foto-First Edition, present images and supplements them with an appropriate excerpt from the volumes. Includes over 160 images, mostly photographs by the great photographer Lewis W. Hines, and drawings by the renown artist, Joseph Stella. This publication is in the public domain, as are all the Findings in Six Volumes, texts and images included.

SAMPLE EXCERPT #1 :

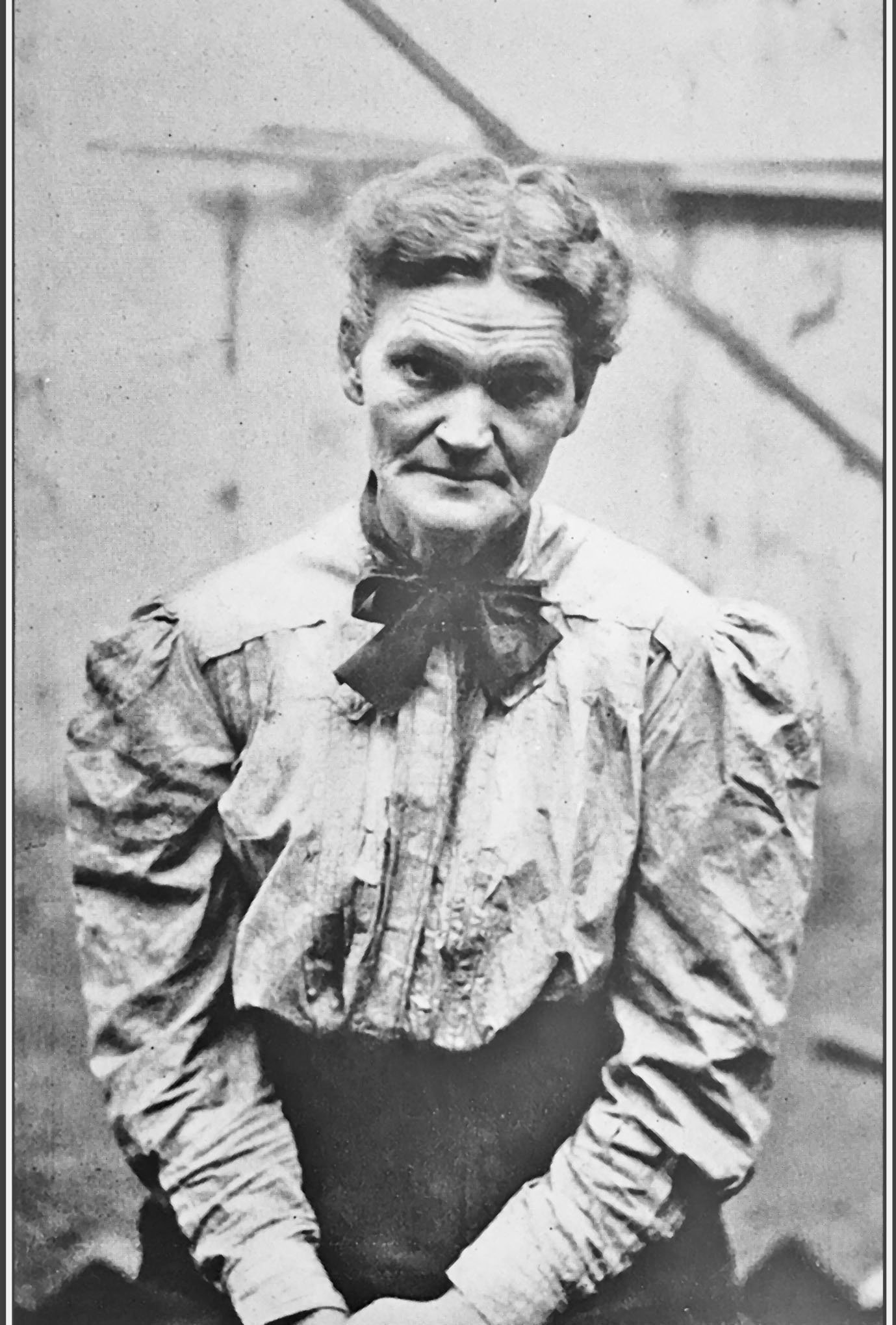

Fig. 07-27: One of the mothers.

There was one wild-eyed little Scotch woman, Mrs. MacGregor, who refused to talk with me at all. I learned from a neighbor that she had twice been insane. Some years ago, when they had lived near the railroad, a little three-year-old girl of hers, who was playing before the house, ran in front of a train. The mother reached the child just in time to touch her dress as the engine tore her away. The mother lost her reason and was sent to an asylum. After six or eight months she recovered and came home. Then, one morning two years later, she got word to come at once to the hospital, that her son was dying. He was a lineman at the Edgar Thomson works, and had left home to go to work as usual two hours before. In some way, —no one ever knew how,—he had fallen from a ladder and broken his skull. After this second blow the mother was again insane.

(Eastman, Crystal. Work-Accidents and the Law, p. 234.)

Excerpt #2

Fig. 03-27: A Second Avenue lodging house and mission in 1908.

The main floor was occupied by the Providence Mission. In the cellar section directly beneath, the writer on the evening of his visit counted 28 Negroes occupying double-decker cots (cots slung on iron frames, one over the other). A meeting was in progress in the room overhead and the shuffling of feet, the clanging of brass, and every word of exhortation could be distinctly heard. Sleep for the lodgers was impossible until after the meeting should adjourn; nor did the sterile emotionalism going on above send down any practical help for them. A single small window at one end of the room offered the only means of ventilation, and this was closed. Gasping upon an upper bunk and spitting blood upon the dirt floor, lay a Negro, far gone with tuberculosis. In the farther cellar slept 30 Negroes, every bunk occupied; while in a coal hole at the rear, a cot beside the water-closet was the sleeping place of a Negro employee. He was engaged at the moment in cooking supper over an oil stove for the watchman.

On the two upper floors of the establishment, the superior whites rolled upon verminous cots, or lay in weary sleep, or in the stupor of alcohol or drugs. Negroes and whites alike were all most miserable and dejected looking. As the place had never been constructed for lodging-house purposes, the two upper floors were divided into a number of small rooms. Two were filled with single cots, each renting for 25 cents per night; the remaining rooms with double deckers renting at 15 cents per night for each bed. Both cots and double-deckers ranged so close together that it was difficult to make our way between them and from one room to another. On the two floors there was accommodation—so called— for 130 men; but as it was summer, the beds were not entirely full, there being possibly a score of vacant places on the double-deckers. In the winter time, according to a statement made by the lodging-house clerk, the place was crowded to suffocation.

(Forbes, James. “The Reverse Side,” Wage-Earning Pittsburgh, pp. 341-42.)

Excerpt #3

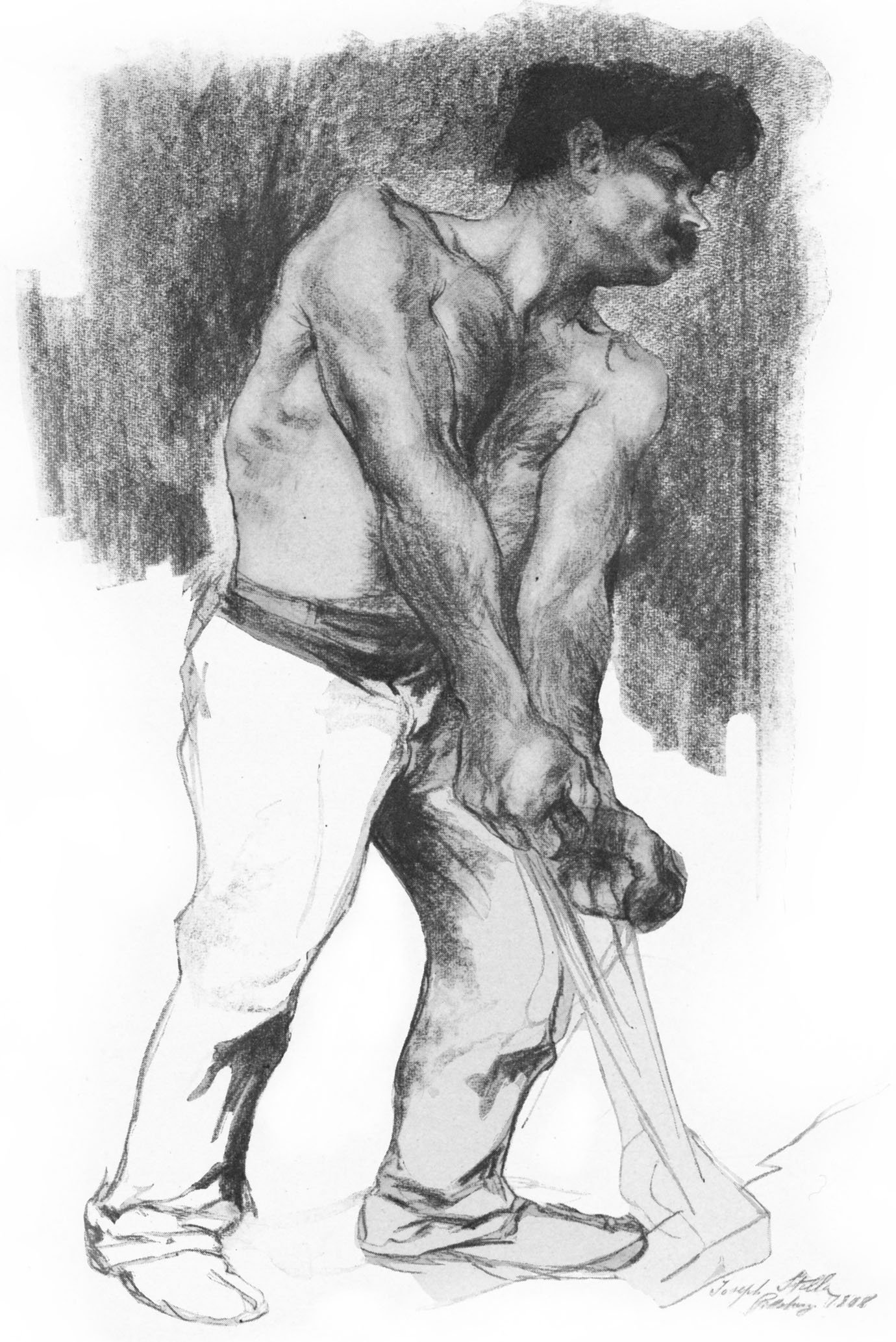

Fig. 04-15: Italian steel worker. (drawn by J. Stella)

The rollers in a Garrett or “looping” mill are literally playing with fire. They are part of the continuous process of turning a three-foot steel “billet,” four inches square, into “rods” a quarter of an inch thick, a process preliminary to making steel wire. After the billet has passed through eight or ten sets of rolls it becomes a long twisting red hot snake of steel, too soft to be guided further by machinery alone, and yet many steps removed from wire. At each pair of rolls, through which the fiery thing must pass, there stands a “catcher.” As the head of the “snake” comes through one pair of rolls he seizes it with iron pincers, and turning quickly places it in the next pair, while the rest of the snake, forced continuously through the rolls, darts twisting down an iron-paved, inclined floor, in a long loop. At the bottom of this incline stands the “hooker,” whose duty it is to watch these red hot loops, sometimes three or four running at once, guide them with his iron hook, and prevent them from getting snarled or tangled. Each process takes but a moment. As soon as the catcher has placed the end of one twisting loop in the rolls, he turns to seize another that is ready for him. This continuous activity grows more rapid and requires more skill as the “snake” becomes thinner and longer, and must go faster to make way for the next one. Thus the worker at the last set of rolls has the most difficult job of all.

This work demands so much of eyes and nerves and muscles, and is done in such intense heat, that the men work in half-hour shifts, six hours of work during a twelve-hour day. Even so, it is only exceptional men who will attempt it, and with all their skill and agility, there are frequent accidents among them. The “catcher,” especially he at the last “pass” or set of rolls, stands encircled by “fiery ribbons of steel, twisting, darting, coiling, at a lightning rate of speed.” Accidents here are likely to be fatal. If the rod catches a man’s leg unprotected by a guard, it will burn though and he may die from shock and loss of blood. The catcher on our list of killed had a leg cut off by a hot rod, and died in four days. A few months later a hooker in the same mill had both feet burned off. A moment’s lapse in agility and watchfulness may mean death, and such lapses will come to the best men, even when working hours are reduced to six.

(Eastman, Crystal. Work-Accidents and the Law, pp. 55-56.)

Fig. 07-27: One of the mothers.

Fig. 03-27: A Second Avenue lodging house and mission in 1908.

Fig. 04-15: Italian steel worker. (drawn by J. Stella)